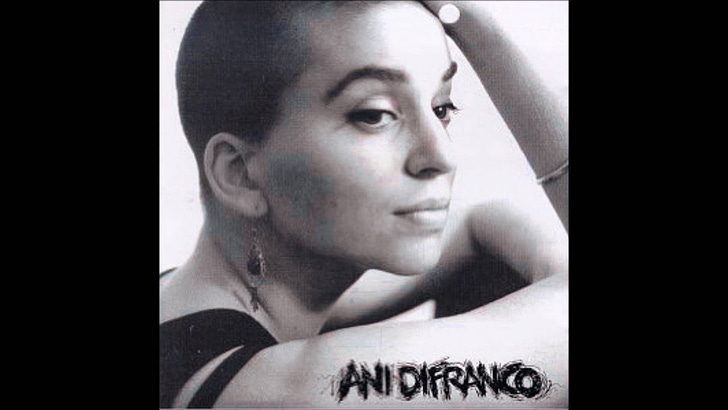

“Both Hands” is the first track on Ani DiFranco’s self-titled debut album, released in 1990. It’s a classic folk song, which is mostly what that album was full of—it didn’t have as many funky, punky, jazzy elements as some of her later albums. I don’t mean to say “Both Hands” is derivative. When I call it a classic folk song, I mean: it’s just an acoustic guitar, and a voice, singing you a story. In this case, it’s a story of love-gone-wrong, of love-almost-at-its-end.

When Dilate came out, and people accused Ani of “selling out”—a difficult thing to do when you release all your albums on your own indie record label—because she wrote a whole album of love and breakup songs and ‘forgot’ about politics, well. That particular criticism was weird to me because—she’d always written love songs. The first track on her first album is one of them. And political vs. apolitical is a false dichotomy, anyway. (To quote a particular Jericho Brown statement for the hundredth time: Every poem is a love poem. Every poem is a political poem…Every love poem is political. Every political poem must fall in love.) Life has many facets, all of which call to us, and need to be spoken/written/sung about by us, at different times. Not to mention that for some of us (like, say, a queer woman such as Ani), writing about who we love and how we love them is political.

But enough about that. Back to the song, which, to me, is one of the saddest and most beautiful songs, ever. It has a simple chord progression: C - Gsus4 - Am - G. That’s it. C - Gsus4 - Am - G, strummed, repeated. None of the crazy riffs she used in her later work. (And no capo! My guitar teacher used to complain about the overuse of the capo in some of her stuff.) Because of that, her voice shines. Her voice, too, sounds different than it does in her later work. It’s clearer, sweeter—it hasn’t matured yet, true, but also, there are no vocal affectations. She sounds young (and she was—only twenty when that album came out), plaintive, real. The song is a young woman with an acoustic guitar and a clear plaintive voice, singing: I am walking out in the rain / And I am listening to the low moan / Of the dial tone again / And I am getting / Nowhere with you / And I can't let it go / And I can't get through. And the song is sad, yes, but it is also sexy: And both hands / Now use both hands / Oh, no don't close your eyes / I am writing / Graffiti on your body / I am drawing the story of / How hard we tried. Sexy-sad; bawdy-blue. That moment at the end of a relationship (or even after the end) when all you have left to give each other is your bodies, and you hope that will be enough, but it never is. It’s not enough to repair the damage already done, or even to gain closure, but you try, you try, you try. You try, and when it doesn’t work, you say: And I'm recording our history now on the bedroom wall / And when we leave the landlord will come and paint over it all.

I first heard Ani at age thirteen, and by fourteen I was a superfan. I bought Not a Pretty Girl first, followed by Dilate (which was released the year I was fourteen). Then I went back to the beginning and bought all her older albums one-by-one, starting with Ani DiFranco. And that is when I first heard “Both Hands.” I loved the song immediately, but I also knew that I couldn’t relate, not fully. I had dated a few people, even been somewhat sexually active for a couple years, and of course I had crushes upon crushes upon crushes…but at that point, I’d never had a real relationship. I have always defined the realness of a relationship not by how long it lasts or how it’s labeled, but rather by the intensity of the feelings involved. And of course at fourteen I’d had plenty of intense feelings about other people, but for a relationship to be real the intense feelings have to be somewhat reciprocal. I do think unrequited love can be real love, but if it’s not requited at least somewhat, it’s not a relationship. At fourteen, I hadn’t had that, yet. Because I hadn’t had a real relationship, I also hadn’t had a real breakup. I also hadn’t had a real heartbreak, the kind that makes you feel like you’re gonna die. My first one of those came not too longer later, and then I racked ‘em up quickly, but I digress… When I first heard “Both Hands,” I knew I couldn’t fully relate to it, yet. I also knew that one day, I would.

Sometime around age twenty, I realized there were many songs that I’d long loved but hadn’t always understood in a bone-deep way, because I hadn’t yet lived them, that I could now relate to. But it was at age twenty-two that I had that realization specifically about “Both Hands.” I was lying on the top bunk of the bunk beds I shared with my roommate, in our cold room, chain-smoking French cigarettes, listening to an Ani DiFranco mix tape, and making notes for a poem I wanted to write, about a long-distance lover of mine. A guy who had said I was his soulmate, and who talked of coming to Chicago, to stay with me, until: Well, I’m seeing this other girl, and I don’t know if I can stand to be away from her for that long. It wasn’t him seeing another girl that I objected to—I’d continued to see other boys and girls throughout the entirety of our whatever-it-was—it was the fact that he no longer wanted to come see me. I had been replaced. So much for soulmates. And yeah, my heart was breaking. And then “Both Hands” came on the mix tape and I thought of my current heartbreak, and all the other aches and breaks and bust-ups and endings of all the other romances that had happened in the eight years since I first heard the song, and I found my way into the poem:

I’ve been digging through

the old records,

lyrical ghosts stuck in the

dusty grooves,

choking me

cos now I can

relate to them

in ways I never wanted

to.

It wasn’t the greatest poem ever, but it did let me write the story of how hard we tried. (It would be another few years before I saw that lover again; before we actually wrote graffiti on one another’s bodies again; before my heart broke over him all over again.)

Hearing “Both Hands” on the radio recently was what inspired me to write this piece. Because this time, when I heard it, I still felt all the old feelings, but I realized I could no longer relate to the lyrics of the song. Or—I can relate in the sense that I’ve been there, done that (oh, so many times), but it all seems so long ago, another lifetime. It’s not to say that I’ll never experience the end of a relationship again (as Rebecca Solnit wrote: even when love doesn’t fail, mortality enters in), or that my heart will never again break. But those feelings, and those experiences, will never be new again. Will never again be that sort of an emergency. Back then, even the falling-in part at the beginning of a relationship made me feel like I was gonna die, and no, I’ll never experience that again. Which is its own kind of heartbreak.

Here, in this weird un-winter of my middle age, I’m listening to lyrical ghosts, choking up because now I can’t relate to them in the ways I used to. Writing the stories of the old heartbreaks. Drawing on those old loves, those bodies in beds, and writing the stories of how hard we tried.