[this piece was written for Reckless Chants #27 (summer 2023), and was loosely inspired by Chavisa Woods’s fantastic story “Things to Do When You’re Goth in the Country.”]

The town where I grew up had one perfect alley. There were a handful of alleys, all within a seven or eight block stretch of downtown, but only that one was perfect. Partly, it had to do with its proximity to the diner. The diner was an old school Greek-American joint. The food was good, greasy and cheap—the coffee was cheap, too—but that wasn’t why we loved it. We loved it because they had a cigarette machine in the back, by the bathrooms. If you slipped in through the back door, you could jam some money in and get a pack before the staff noticed you and thought to check if you were underage or not. You’d get your cigarettes, and dip out as quick as you went in, cut around the corner—and there you were, in the alley.

Just being in that alley made you cool. It was between two blocks of older buildings; all constructed with the cream brick that’s everywhere in that town, and all gone sooty with time. Graffitied scrawls—some spray-painted, others scratched into the filthy bricks—covered the buildings and the dumpsters. There were a couple rusty fire escapes, which led to the apartments on the upper floors. And the alley was so narrow, it was darkish even at midday—and at night, it only got a faint glow from one streetlamp. So you’d stand there with your fresh pack of illegal cigarettes—lights or menthols, for most of the kids; Marb Reds or Camel nonfilters if you were hardcore, like me. You’d pack them, flip a lucky, pull one out to smoke, then stash the pack in your bag, or, if you wanted to be extra cool, roll it up in a t-shirt sleeve. Then you’d lean against the dirty brick building, light your cigarette, stand there and smoke it in the darkening alley. You’d smell the grease and burnt coffee from the diner and the garlic from the Chinese place a few blocks north. And looking around at the graffiti and dumpsters, the fire escapes and the wreath of smoke from your cigarette all glowing in the sulfurous streetlamp light, you could forget where you were for a second. For a second, you could almost pretend you were in a real city; a place where things happened.

In the years between the start of my transformation into a punk rocker, and when I first moved away, I spent a lot of time in that alley. Sometimes I’d hang there alone, but most often I went there with a rotating cast of friends and acquaintances and crushes.

Often, I went there with Amelia and Ashley and Sid. Sometimes, Joaquin would be there, with his peroxide hair and junkie-thin body; his ice-blue eyes and devil grin. And that was sometimes awkward, because I was mega in love with him, and he didn’t seem to have any idea. Then again, he always had drugs with him, and he always shared, which took the edge off the awkwardness. Sometimes, Flash was there, and I was super in love with her, too; even more so than I was with Joaquin. I don’t know if she knew or not, ‘cause I didn’t tell her until years later. But she’d do things like grab my hand and say: “Let’s hold hands and be gay!” And I’d have to stop myself from kissing her or shouting my frustrated desires at the downtown night sky. Because, yeah, she did things like that, but she was straight. Sometimes, Flash brought her two best friends with her—Kamala and Janie. Kamala had long, messy hair, usually dyed some shade of purple. She rocked the grunge style with babydoll dresses and combat boots, or old t-shirts and ripped-up jeans, and her ever-present “everything sucks” sneer. Janie was cute and short, with a button nose and a shaved head. Aside from me, she was the punkest of the alley crew. She wore boots and tight pants and wife-beaters, with a leather jacket on colder days, and a padlock on a chain around her neck. We shared a mutual obsession with The Clash and The Young Ones. I should mention that Kamala and Janie were also totally crushed out on Joaquin, and knew I was, too. I was pretty sure Kamala hated me for it, but Janie didn’t seem to care, and after a while I developed a crush on her.

Oh, there were so many people who drifted in and out of that alley. Like Grant, who got me into ska. He sported a mohawk a la Fishbone’s Angelo Moore, before shaving it off and going the skinhead route. Like Colin, the goth-industrial prettyboy—until we made out at a party and it was too weird to be around each other for a while. Like Bryan, with his dreadlocks and beautiful smile, and the sort of personality that made him everyone’s friend. Like Marina—on the nights her parents let her out of the house, that is. Like Filia, when she came to visit. We’d go there to smoke and feel cool, after we’d stopped at the one actual record store in town, before we walked over to the cafe (it was the ‘90s, even my nothing town had a hipster/slacker coffee shop) to work on a zine or flirt with the punk and goth boys.

Sometimes Yesenia would be there; two black braids trailing down her back, fingernails painted black. Sometimes Tobias would hang out, when he wasn’t too busy doing drummer-stuff for his band. (They were one of the only bands from our town who got somewhat known nation-wide, and I was so jealous because he got to go on tour.)

Who else? Sometimes the trio of cute, stupid skater boys would show up. They were so joined at the hips that they were almost one person; like some three-headed beast on wheels. Or the weird kid I knew from theater classes. He wore a fucking cape all the time and didn’t talk much, and most people thought he was a total freak. But there was this aura of danger and mystery about him. Everyone who hung out in that alley had fucked-up families/home lives, to some extent, but from what I knew of him, his was the most fucked up. Like, gothic novel levels of fucked up. Plus, I’d heard rumors about some of his sexual proclivities, which were…intriguing, to say the least.

In later years, Joey sometimes joined us. He was a few years younger and sort of looked up to me as a punk rock older sibling. I gave him mix tapes and taught him about zines. One night we stood in that alley, smoking, and he told me about all his problems with his girlfriend and his parents, and how he’d started cutting and doing drugs. He said: “I knew I could tell you, because I know you do that stuff, too.” And I told him he could tell me anything, but: “Don’t be like me, dude. I’m a fuck up.” Not too long after that, I guess his parents decided he was too much of a fuck up. They sent him off to military school and I never saw him again.

Before all that, there were other people we sometimes hung with. Like some of the older punks and goths and indie rockers that we knew from the cafe and from local shows. They were older teenagers, or in their early twenties, and we liked being around them because they had access to booze or, at the very least, cars. There was the guy who, with the length and shade of his hair, and his ‘70s clothes, looked sorta like Anthony Rapp’s character in Dazed and Confused. He always gave excellent feedback and encouragement on my poetry. There was Nolan, who played in like, five local bands and ran a record label out of his apartment. We went on a date, once, because our friends thought we were perfect for each other. But—to misquote Gertrude Stein—there was no there there. There was the tall sad queer boy who kinda looked like Sid Vicious, and later became my lover. There was Madigan, who I befriended because she was one of the few riot grrrls in town, and later we did drugs together and wound up fucking and it ruined our friendship.

You may be sensing a theme here—that a lot of my friends were also my crushes or lovers. This is part of being a punk in a mid-sized city. There aren’t that many people worth being friends with or having the hots for, so there’s a lot of crossover between the two. Similarly, not all my friends were punks. Because, when the pool is that small, you hang out with whatever weirdos you can find, punk or no.

That alley. Me and my weirdo friends were there a lot. Sometimes in the mornings, post diner breakfast, after staying up all night watching slasher flicks at Sid’s house. But more often, we went there in the evenings. We’d smoke in the alley for a while, before trickling out and spilling into the rest of the downtown. Sometimes we’d get stoned on the courthouse lawn. We’d pass around an acoustic guitar and take turns playing folk songs, which I always ruined by screaming them like they were punk songs. Sometimes we’d go to the cafe, to watch a band play. Or for poetry night, where I’d share a few silly poems about crushes on emo boys or something and then decimate everyone by closing my set with some long-form piece about self-injury or police brutality. But a lot of the time we’d just wander; spread mischief as we headed east, toward the lake. We’d make our own markings on the cream brick walls of downtown; or Sid would throw one of the skater boys in a dumpster. Or some of the girls would take off their shirts and walk around in their bras, and some car full of chuds would catcall. Yesenia would give ‘em the finger, and my tall sad queer lover would pull himself up to his full height and get this look in his eyes, and the chuds would speed off because when he did that you knew he wasn’t someone you wanted to fuck with. Other times, a car full of chuds would see our gang of misfits and not know how to process it. So they’d shout something real clever, like: “Homosexual fucking faggots!” When that happened, even the straightest amongst us would grab the nearest person of the same gender and kiss them, until the chuds got so grossed out they drove away. Then we’d all laugh like crazy. “Homosexual fucking faggots, oooh.” “As opposed to all those heterosexual faggots you hear so much about.”

I participated in all that stuff but part of me was always watching it all, recording it all in my head. On some of those nights, I felt like we were in some fucked-up teen movie with a killer soundtrack. Like Empire Records, or subUrbia (1996), or even better, Suburbia (1983). And on those nights, I was truly, truly happy for a moment.

Finding a good alley to hang in and a group of freaks to hang with is an essential part of being a punk in a mid-sized midwest city. But there is so much other stuff to do.

You gotta spend time cultivating your look, and your musical knowledge. You can attain the musical knowledge through a combination of: research (via books about classic punk, interviews with your favorite current bands where they talk about their influences, and fanzines), college radio, trading tapes, and scouring the racks of record stores and thrift shops.

As for your look—well, when you can manage to get to cities with stores that actually sell punk clothes and accessories, you should pick up a few things. Mailorder is good for that, too. But you can achieve the rest with thrift shopping and DIY. Don’t be afraid to get weird with it. Make your own patches! Rip up your tights! Put bleach splotches on your jeans! Put Kool-Aid in your hair! Combine things that shouldn’t go together! Like, I would wear plastic pastel baby barrettes in my spiky hair, and wear jelly bracelets alongside my studded ones. Or I’d wear a hideous Day-Glo polyester shirt from the ‘70s, with tight pants and high-top Chucks. Or I’d wear a leopard print top with plaid pants. Of course, the classic combo of “black clothes with boots and chains” is always good, but in general, punk style (the way I did it) wasn’t so much about looking cool as it was about looking a little bizarre and offputting, yet also whimsical.

I mean, the main thing is rebelling. Rebelling against shitty dudes, shitty chicks, shitty parents; against heteronormativity, capitalism, conventions of any kind. Against everything everyone expects of you, the once-gifted child. Against everything they say you should care about. Make yourself bizarre and offputting. Fashion yourself into a middle finger in the shape of a teenager. Go to protests. Declare yourself an anarchist. Spray paint the town. Write zines, write poorly-researched political rants, write poems where you make copious use of the word fuck. Start a band, or play guitar alone in your room. Take your shirt off and stand in front of your mirror and practice imitating the yowl Iggy Pop makes at the beginning of “T.V. Eye.” Cut off all your hair. Steal from chain stores. Drop out of high school. Flip off cops that harass the kids who skateboard in the town square. Get your own skateboard. Fall off it a lot. Skin your knees. Fall in love with the sweat and bruise of a slam pit.

Take every insult anyone has ever thrown at you and turn it into a weapon, a fuck you. When they call you a dork, say: “Yeah, I’m a dork, fuck you.” When they call you a freak and a queer, say: “Damn right I am.” When they call you slut, say: “Maybe I am, but honey—you’ll never know.” When your parents and certain old friends say they hate your newfound punk identity, when they wish for the ‘old you’ back, say: “Fuck you, I’m punk.” When the Tru Punx call you a poser, sing: “I am a poseur and I don’t care.” When they say: “You're not punk, and I'm telling everyone,” sing: “Save your breath, I never was one.”

There are other things I did which started out as rebellion, but turned into self-destruction. Like cutting myself with safety pins and razorblades, or burning myself with cigarettes. Like doing drugs, drinking, and smoking. If you require some kind of minor bodily harm to feel okay in your skin, maybe stick to the aforementioned skateboarding- and slamdancing- related injuries, or get into hedgecore, rather than trying any of the things on the latter list. Obviously, I can’t stop you, and I’m sure you have your own reasons, and I’m not saying you have to be straightedge, but. Don’t be like me, dude. I’m a fuck up.

And of course there was trauma involved in why I partook of the more self-destructive pastimes. I mean, duh. Trauma from the past, and ongoing trauma. But I learned that no matter how much I told people, or wrote about it in my zine, no one understood. They never thought my traumas were bad enough to excuse how much of a fuck-up I was. So after a while I would only mention it in offhand, jokey ways. Either that, or I’d bring some heavy shit to poetry nights at the cafe or library; hit ‘em with something so dark the room would go dead silent and you could hear a safety pin drop. Like I said, I’d read a few poems about crushes or something, then close with a graphic lyric about cutting myself or killing rapists. Open. Mic. Pin. Drop.

In those days, there was this constant burning in my chest. I was afraid of everything, but courted danger. I felt trapped in my town, and in my own skin. I wanted to escape. I thought of suicide often, and tried it, a few times. Other times, I stood on the edge of my garage roof, willing myself to jump. And some days I did want to die, but most days it was more like I wanted to live. I wanted my real life to start, and I felt powerless to make that happen. So I escaped in other ways. I rode the bus, or caught rides in my friends’ cars, to Milwaukee or Kenosha. I caught the bus to the Metra train station in Kenosha, then took the train to Chicago. I hitchhiked whenever possible, to Kenosha, Milwaukee, Madison, Minneapolis, Green Bay. Anywhere was better than here.

And then there was the crushing loneliness. I felt like an outcast, even when around friends. Part of it stemmed from the fact that the town I lived in wasn’t my hometown. I’d moved there when I was almost 11; had already lived in five other towns and two other states before that. Whereas most people I met had lived there their whole lives, and had known each other their whole lives, too. Part of it was being a writer—always recording everything in my head, even as it was happening.

My very best friend, Filia, lived some 700-odd miles away, and I only got to see her once a year; or maybe twice, if I was lucky. The rest of the the time I was half-miserable, waiting until I could see her again. And Marina was my best friend in town, for a while, until—

When Marina and I met, we bonded over two things. We hated our town, and loved the Violent Femmes. I mean, of course we loved the Femmes, they were practically local. In fact, Victor DeLorenzo, the drummer, was from our town. And we knew when they sang about that ugly lake, they were singing about the same one we saw every day. And yeah, we hated our town; she, like me, dreamt of escape and what it would be like when her real life began. We made lists of the cities we wanted to visit, the bands we wanted to see, the drugs we wanted to do, the colors we wanted to dye our hair.

Her parents were super conservative Catholics—even the most devout Catholic members of my own family were not that conservative—and they never liked me. They said I was a bad influence. Because I swore and listened to punk and dressed like a screwball. But we laughed about it! When they did let her hang out, we’d go to shows at the YMCA, hang in the alley, stay up all night at Denny’s, write zines about how much we hated our town and loved the Violent Femmes. And when they went out for the night, we’d hang out at her house. We’d get drunk off Schnapps lifted from their liquor cabinet (they had so much booze in there; they never noticed). Then we’d sneak over to a nearby church and rearrange the letters on their signs to say something sorta Satanic or just surreal and silly. Or we’d take the half-broken communal paddle boat out on the algae-covered manmade ‘lake’ behind her subdivision; lay there and talk and stare at the stars. Or we’d blast the Femmes and sing along: I take one, one, one ‘cause you left me / And two, two, two for my family / And three, three, three for my heartache / And four, four, four for my headaches / And five, five, five for my lonely…

Our friendship wasn’t perfect. She didn’t know I was bi, ‘cause she’d made some weird comments about lesbians and I knew she’d flip out if I told her. But I had hopes that one day she’d come around. I’d already gotten her into zines, plus some music that, if not overt, at least had queer subtext. I was making her cooler. And then she started going to these Born Again Christian youth groups—her parents encouraged it, which I found odd, because normally Catholics and Born Agains are mortal enemies. And I started getting into harder drugs and listening to harder music, and when I saw her it was no longer: “Haha, my parents think you’re a bad influence on me.” It was: “You’re a bad influence. I’m gonna go to hell if I keep hanging out with you. You’re gonna go to hell if you keep on like this…” I didn’t believe in hell, but it was annoying. So to hell with her. Our friendship ended, and we lost touch, and I didn’t see her again until years later, when her parents invited me to her wedding.

When it came to romantic and sexual relationships, things were much the same. I was desperately lonely. I craved love and intimacy, but was also terrified of it. And on some level, I didn’t feel I deserved a healthy, requited relationship. So I tended to fall for people who were unattainable in some way. Like, they lived far enough away that even if they liked me back, we couldn’t be together. Or they lived nearby, but they were: already dating someone, not interested in people of my gender (like Flash, and a few others), or on so many drugs they didn’t know what day it was, let alone have the ability to be in a functional relationship (Joaquin). Or they were—in my mind, anyway—too cool to actually be interested in me (everyone else).

The people I dated or hooked up with were often people I had no real feelings for, or who treated me like shit, or who didn’t live nearby. (Geographical distance was a bummer when it came to people I liked, but a blessing when it came to people I wanted to fool around with and forget. ‘Cause then, there was no way they could demand a real relationship. And no chance I’d run into them and have to deal with all that potential awkwardness.)

And when I did meet someone who was local-ish, and they treated me well, and I got an inkling I could end up actually liking them? I pushed them the fuck away.

And no one in my town got it. Any of it.

They didn’t get my desperate need for escape, why I wanted out, now. Sure, they’d leave town for shows and whatnot, but they always seemed content to return.

At the same time, they didn’t get the things I loved about our town; didn’t seem to love them in the intense way I did. Like the alley, and the whole downtown. Like the ugly lake. Like all the diners and greasy spoons; how for a while we still had a real drive-in restaurant where the waitstaff brought your fries and sandwiches right to your car. Like the roller rink, and the haunted places, and the secret drinking spots in the woods out by the power plant. The vacant lots; the rubble of long-abandoned buildings soon to be torn down. The wild, weedy places near the lake, where sometimes in late summer you’d find bushes sagging with blackberries free for the taking, dark burst in the mouth. Like the post-war subdivision out by the old Horlick Malted Milk factory, where all the streets were named after planets or stars. I’d drive past Polaris Avenue and think of The Adventures of Pete and Pete. Or I’d park my car and walk around, look up at the scummy water tower and think of The Replacements; think of climbing it, screaming I can’t hardly wait.

No one knew what I was all about, like flipping off cops, and reading Kerouac.

Even Flash, my dream girl, once told me I should get over the punk thing because punk was dead.

Even after I’d started college and started hanging out with this guy who seemed like he knew what was up—. On our first official date, I took him to the cafe, and then showed him the alley, and he said: “It’s an…alley.” I should’ve known right then that he didn’t get it, either.

Despite the burning ache and the lonesome restlessness, there’s so much for you to do.

With your friends: poke ugly-perfect tattoos into one another’s skin with sewing needles and India ink. Use sewing needles to pierce holes in each other’s ears, noses, bellybuttons; wear safety pins in the holes until they get infected, hot and oozing with pus. Skip any and all school dances, including prom, to go get wasted at punk shows in Chicago. Invite them up to your garage roof to get wasted and stare at the stars. Haunt the train tracks. Leave markings on boxcars and gondolas; imagine hopping onto an empty boxcar and going anywhere but here. Pick bouquets of chicory and Queen Anne’s lace. Go to playgrounds, late at night, to sit on the swings and get stoned and look at the moon and swing high enough it feels like you could almost touch it. Drive, whenever any of you have access to car. Drive to nowhere, around and around, with the radio on, playing Dinosaur Jr. Drive to the next county west of yours, to look for the local cryptid. Even though the last reported sighting of this beastie was six or so years ago, you have hope she’s still out there, prowling the backroads. Park on the dusty shoulder of a country road at night; cut the headlights. When you see a canine shape slinking through the rural nightblack, or catch the yellow glint of eyes in the moonlight, say: “It was probably nothing.” But think: maybe it was. Drive to the second-run movie theater. It doesn’t matter much what’s playing—it’s cheap, and sometimes you need to sit in the dark watching a movie and eating rancid, oily popcorn. Drive to the mall. You fucking hate the mall, but sometimes there’s nothing else to do. And you can walk around talking shit about all the trendy kids, or shoplifting from the chain record stores or Claire’s. After, you can smoke cigarettes in the parking lot, and watch the way the sunset turns the oil and gas puddled in the cratered pavement into fire-lit rainbows.

Alone: Wear a thrifted ‘80s prom dress with fishnets and combat boots and go to Walgreens to steal eyeliner. Then stand in the parking lot smoking a cigarette and feeling like a “Warrior in Walgreens,” a suburban American spinoff of an X-Ray Spex song. Go to the used CD store out by the mall, where the cute gay punk guy works. He smelled the queer on you the first time you went in, and started setting aside all the good shit to give you first pass at it. Ride your bike to the library. Ride your bike to the haunted grounds of the old Episcopal boys’ college. Sit in the cool green lattice-worked shade near the chapel, to talk to the ghosts, to read Blake, Shelley, Keats, Yeats, Baudelaire, Rimbaud. Go days, weeks, even months sometimes, without drinking or using drugs. Get sad about your friends who are drinking and drugging themselves into oblivion. Get annoyed with your friends who aren’t that far gone but who, when they’re drunk or high, never want to do anything. (Even at your most intoxicated, you still wanna go out and fuck shit up.) Contemplate going straightedge. Then remember that most of the edgers you know are as fucked in the head, and as boring, as everyone else. Say: “Fuck you, Ian Mackaye. I smoke, I drink, I fuck, and I can still fucking think.” Slip some brandy into your coffee. Climb out onto your garage roof, to read Kerouac and Ginsberg; to pretend the clouds on the horizon are mountains. Write letters to faraway friends and lovers. Collage the walls of your bedroom with posters and pages torn from fanzines. Write on the walls in Sharpie: I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness. I hate myself and want to die. Jack off to fantasies of your favorite rockstars, or to the imaginary perfect punk rock lover you already have an inkling doesn’t actually exist.

At night, lie in bed with your window open and your Walkman on, listening to Alkaline Trio blending with the sound of the foghorn, and the trains going past on the nearby tracks. Smell the lilacs in the backyard, the shit breeze from the wastewater treatment plant, the rot of dying alewives on the beach, the toxic, gluey scent from the tractor factory. Fall asleep and dream of serial killers slicing through the windowscreen, then slicing your throat. Dream of car crashes and train wrecks; of bodies floating in the quarry lakes. Dream of roadkill, guts baked on the backroads; of carrion birds circling, circling. Dream of that time you took the bus to catch the train to Chicago. How you were listening to a mix tape a zine pal made that was a perfect blend of street punk, crust punk, industrial, and goth, and the gray cloudchoked November sky cracked open for a split second and bathed everything in gold—the corn and cabbage fields, the tar on the road, the bus and everyone on it.

Years later, long after you’ve escaped the town and then returned, you’ll sometimes find yourself longing for those days. Not the crushing loneliness or constant restlessness, but—. Well, you no longer hate the town—now, it is home—but at the same time, a lot of the magic has disappeared. The diner closed a long time ago; before you even left, soon after you were old enough not to have to sneak in the back door to get cigarettes anymore. The cafe has since shut down; so has the record shop. You’ve lost touch with, or lost, all the friends you had back then. The alley’s still there, and you still visit it sometimes, but now it is, in fact, just an alley. You still like to wander around the grounds at the old boys’ college, and you still sometimes feel a prickle where the hair stands up on the back of your neck, but the ghosts no longer talk to you.

Still, on some nights, though you live in a different neighborhood than the one you grew up in, when you leave the window open, you can hear the foghorn and the trains. And on those nights, you’ll fall asleep and dream. Dream of your name, graffitied over and over in soot and spray paint on the walls of the alley. Dream of the ghosts at the boys’ college, what they used to say. Dream those days like films in your head, with all their fucked-up beauty and killer soundtracks. Know you’ll never, never stop writing them.

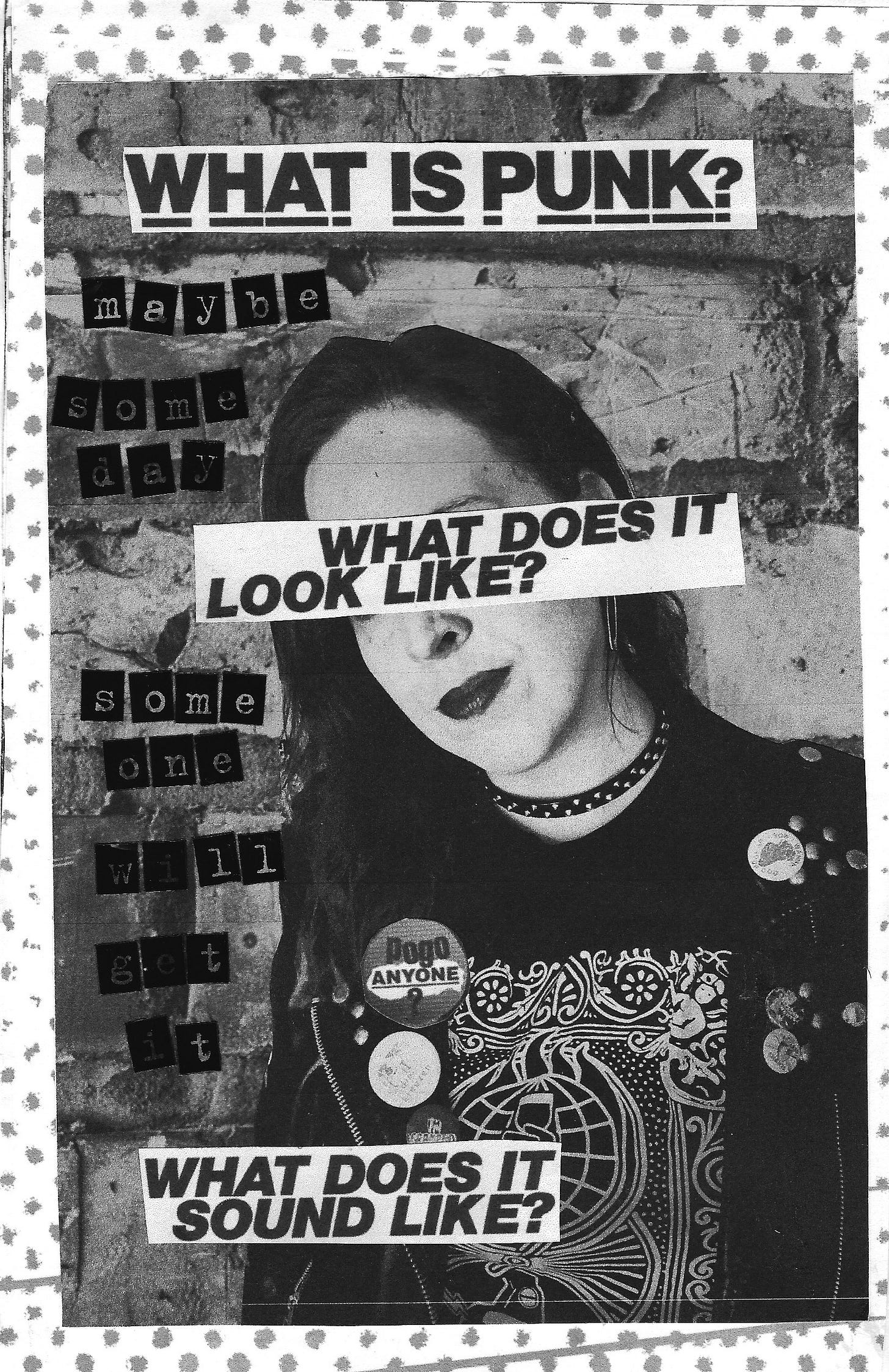

Maybe, someday, someone will get it.

I love this Jessie. The details are so vivid. Cigarette machine! As someone from a small town in the midwest who was a "bad influence" I can relate to a lot of this.