That night, Rain Street went on for miles.

on Shane MacGowan, punk poetry, addiction, and romanticizing everything

The first thing I saw on the morning of November 30 was the news that Shane MacGowan had died. I hadn’t had my first cup of coffee yet, or even risen from bed. I woke up, picked up my phone, and opened a social media app. That in itself was unusual, as I don’t often check news or social media until I’ve been awake for a couple hours. Why did I choose to do it that day? I won’t say it was a premonition. I had odd, sad dreams the night before and woke up with the feeling that Something Had Happened. But I often have odd, sad dreams, and Something is always Happening in this world we live in. (Too many fucking things are happening all the time, actually! I would like a break from the things!)

Premonition or no, I hopped on social media first thing in the morning. And the first thing I saw there was a photograph of Shane MacGowan in a striped shirt, snarling his beautiful black-toothed snarl into the microphone, and beneath that: RIP Shane. I searched the news for confirmation and yes, it was true. Shane MacGowan, the holy hard-drinking punk poet (as Enrico Brizzi described him in his novel Jack Frusciante Has Left the Band) had departed this mortal coil. Then I went downstairs, poured my coffee, and said to my spouse: “Please get some Guinness when you go to the store today. I’m gonna need it.”

While sipping my coffee, I began jotting down notes for things I wanted to write about The Pogues and Shane. There were so many things that came up, and I realized I couldn’t fit them all in one piece. No surprise there. Shane and The Pogues have been a massive presence in my life for damn near twenty-seven years now. But I knew that I had to narrow it down a bit and get at least one thing written, so I could publish it here. I had the second installment of These Fucking Songs almost finished, but fuck it, I’d save that for a later time. For now, I had to say something about Shane MacGowan, and the motherfucking Pogues.

At first, I thought I’d write it as a proper installment of TFS. Not about their whole discography, because The Pogues released many albums, and trying to write about them all would be too daunting. And writing about a singular album wouldn’t work. I love too many songs from too many of their albums, and writing about one of their Best Of collections seemed like cheating. Okay, so I’d pick one song and write about it. But which song? Can’t write about “Fairytale of New York,” that’s too obvious, even if it is the best Christmas song of all time. What about “Haunted,” the song they wrote for the Sid and Nancy soundtrack? (Or the version that Shane and Sinéad O’Connor recorded together in the ‘90s?) That one hurt too much to even consider writing about right then. And speaking of Pogues songs which break my fuckin’ heart, what about “A Rainy Night in Soho,” which is not only my favorite Pogues song, but is also one of the finest love songs ever written? But I’ve already written about that song and my personal connection to it. Shit. Maybe I should go for one of their less melancholy-sounding tunes. Maybe I could write about “Sally MacLennane?” I have enough memories attached to that one. Memories of sitting in a pub in Kenosha, Racine, Sister Bay, Gettysburg, Philadelphia, wherever, with my best Filia and whoever else happened to be around, playing that song on the jukebox, using our hands to pound out the rat-a-tat-tat on the grimy bartop, screeching “Far Away!” during the choruses.

As all this was going through my mind, I checked my phone again. There was a text from Filia. A link to the news of Shane’s death, and then a message from her, saying the legendary :(. We texted back and forth for a bit. About how that news was the first thing we saw upon waking. About how he’d been sick for so long that it wasn’t a surprise, yet we were still shocked and sad. How we were sadder about it than we ‘should be,’ considering we didn’t know the man personally. Maybe emotional is a better word for what we’re feeling, she said. I agreed. Sad, emotional, whatever you wanted to call it, Shane’s death brought up a lot of stuff for both of us.

One of the things it brought up for me was the memory of finding out about Joe Strummer’s death. It was December 2002. I had just flown back to Chicago from visiting Filia on the east coast. When I got back to my apartment, there was a message from her on my answering machine. “I have bad news,” she said. “Call me back as soon as you can.” I called her immediately, and she broke the news to me, and we sat there together, trying to imagine life in a Joe Strummer-less world. I’ve written about that before, too, but it bears repeating, because—there we were, twenty-one years on. There we were, together across the miles, processing the loss of another beloved songwriter who’d provided the soundtrack to our lives.

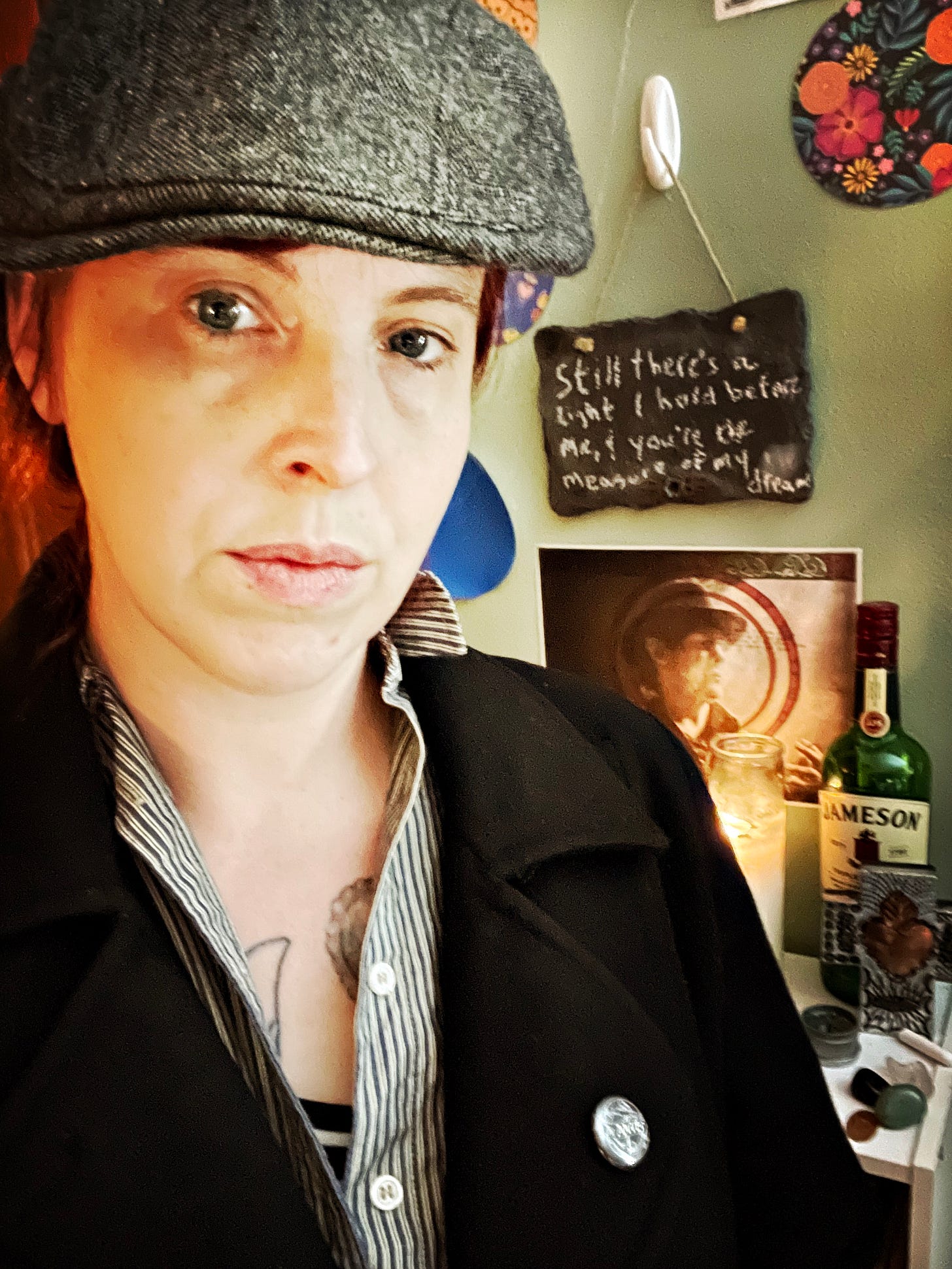

I didn’t end up writing anything that day, other than notes. Instead, I listened to The Pogues, made a Shane MacGowan/“Rainy Night in Soho”-inspired art piece, and made an altar in tribute to Shane.

That night, I had two opposite—but equally intense—impulses. One of them was to get fucking wasted. To get as wasted as I would have in those “singing along to ‘Sally MacLennane’ in the pub” days; to get so plowed all the stuff that Shane’s death brought up for me would sink beneath a stream of whiskey. The other was to not drink, at all; to not only stay sober that night but to never touch a drop of booze again. Because of Shane’s life-long struggles with addiction, because of so many of my beloveds’ struggles with addiction, because of my own struggles with addiction—my own affinity for hurling [myself] toward oblivion in the back of some grim and sticky dive, as Amanda Petrusich put it in her wonderful tribute to Shane.

I didn’t go to either extreme. I didn’t get wasted, nor did I abstain. I poured myself a Guinness, and a shot of Jameson. I left the rest of the Jameson in the bottle, and placed it on my altar—for Shane, and for my own dear departed. (Because my ghosts, they’re the sort that can be summoned with some real Irish whiskey.) I lit a few candles, said “slainté,” and then I drank.

Unlike when Joe Strummer died, after Shane’s death, no one crawled out of the dark corners of the Internet to tell me it was bullshit to mourn someone I didn’t know. Instead, most of my friends commiserated with me, and I witnessed outpourings of love and grief from Pogues fans the world over—most of whom didn’t know Shane, either.

Also unlike the aftermath of Joe’s death, when I had people tell me that Joe wasn’t punk, and that none of the music he’d made post-Clash was punk (and that even most of The Clash’s stuff was on thin ice, punk-wise), no one said that about Shane. Partly it may be because I run in different circles now; there are fewer Tru Punx (TM) among my acquaintances than there were back then. Partly, though, I think it’s because Shane transcended punk. He was punk, no question about it, but the music he made went into stranger territories than straight-ahead punk rock. He was a (bum and a) punk, yes, but he was also, and more so, a poet. (In my mind, Strummer also transcended punk, and was also a great poet, but I think a lot of people still looked to his image circa the early days of The Clash, and thought that everything that came after was lesser, rather than more.)

What I did come across were some comments on various posts and articles about MacGowan’s death focusing on his struggles with addiction, and demonizing him for it. Like: “Good riddance, he was just a fucking junkie drunk.” Or: “He smoked and drank and drugged himself to oblivion, he was lucky to have made it to 65!”

And then there was a post that shared a passage from the lovely eulogy Victoria Mary Clarke (Shane’s wife and life partner) made at his funeral. The gist of what she said is that he treated homeless people, including homeless addicts, with respect and kindness. Then she went on to say that yes, he himself was an addict, but that wasn’t all he was; and that no one is just an addict. She said: “…next time you see someone and think ‘that person’s just an alcoholic or a drug addict,’ stop, give thought to it and consider giving a bit of compassion and respect.” The comments on that post were some of the worst. They accused her of ‘glamorizing addiction,’ because apparently telling people that addicts deserve to be treated like human beings and saying something more nuanced than Addiction Bad is the same as glamorizing it. Some people said: “Well, maybe Shane was a genius and a beautiful soul, but most addicts aren’t.” Others said: “Shane wasn’t even a genius, and come to think of it, most of his songs glamorized addiction, too.”

The night after Shane’s funeral, I was getting dressed for a poetry reading. I put on my Keep Books Dangerous/Support Small Press t-shirt (which I long ago cut the sleeves off), and a pair of tight black pants. Then I added black boots, a red beret, and my black leather jacket with all the pins and studs on it (including my Pogues pin, natch). Can a person be both a punk and a poet in equal measure, or will one always win out over the other? I wondered. Because yes, I was dressed in a punk style, and I’ll always be inspired by the undying spirit of punk rock, but over the past eight years, being a poet has been more central to my identity than being a punk. (Says the guy who recently wrote a whole zine about the punk rocks.)

And then at the reading, I read one of my poems which not only glamorizes some types of addiction I’ve experienced—Bottles. Pills. Needles and smoke.—but also makes mention of that very aspect of my writing: How you romanticize things that are bad for you. That’s something I’ve been accused of for most of my writing career—romanticizing things that are ‘bad.’

Whenever someone accuses me of that sort of thing now, I think of what Mark Doty wrote of Lynda Hull’s poetry (which describes things like homelessness and heroin addiction in lush, hallucinatory language): If the difficulty of personal history is glamorized, in these poems, it is because glamour is a way of making history bearable. I think, also, of the discussion/interview Nicholas Michael Ravnikar and I recorded for Paper::Knives. I mentioned to him that I’d been accused of romanticizing things such as addiction, poverty, shitty relationships, etc., because I rarely say ‘this is a bad thing,’ and because I often describe difficult times in my life in ways that show they had beauty, too. I’m paraphrasing, but his response was something like: “Are you romanticizing those things, or are you elevating them to the status of art?”

So many people seem to think that if you don’t equivocate or moralize, that if you speak about things with nuance, that means you’re condoning or encouraging the unhealthy or the awful or the immoral. So many people seem to think if you can describe the beauty of the bad times, you’re saying the bad times were good, actually. But no one’s life is just one thing. Life is all of it, by turns—pain and joy, beauty and ugliness, humor and sorrow, mundanity and sublimity. Often, it’s all of it at the same time. And real art recognizes that. Real art says: this is my life, these are the lives of others that I’ve witnessed, in all their shit and heartbreak and glory. Real art can admit regret, but also recognizes that if someone hadn’t experienced what they’ve experienced, done what they’ve done, they wouldn’t be the same person.

Real art, such as Raymond Carver’s poem “Rain,” says:

Would I live my life over again?

Make the same unforgiveable mistakes?

Yes, given half a chance. Yes.

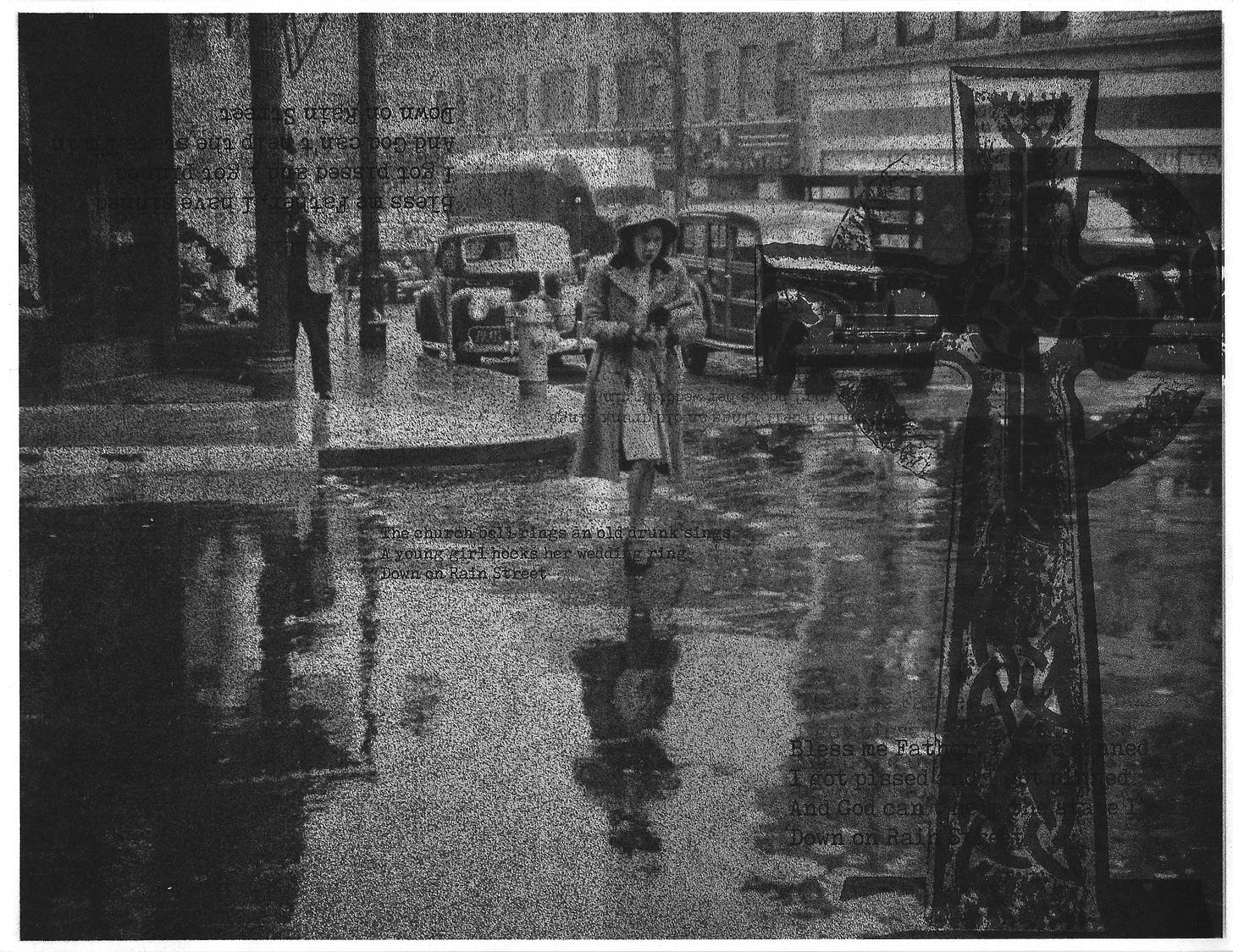

Which brings me to the Pogues song I chose to write about: “Rain Street.”

To me, this song is the epitome of elevating life—real life, in all its shit and heartbreak and glory—to the status of art. It’s also The Pogues at their best and most Pogue-like. It has a fantastic fusion of instruments and sounds; James Fearnley on accordion, Terry Woods on mandolin, and of course Spider Stacy on tin whistle (listen to the bridge, that tin whistle bit is so lovely). All those Irish folk instruments The Pogues were known for, yet it doesn’t sound like a traditional Irish folk song. (And that was one of the things The Pogues did so well—taking elements from Irish folk music and from so many other kinds of music, and fusing them into something wholly their own.) The music is bright and percussive, jaunty and upbeat, which creates a perfect juxtaposition with the lyrics—Shane MacGowan and his slurred, raspy croon, singing about a sad street full of down-and-out characters: a young girl pawning her wedding rings, kids sniffing glue, drunken priests with venereal diseases, and the singer himself, trying to take a late night piss (or, in some live versions, trying to take a late night fix). But there’s humor there, too: I sat on the floor and watched TV / Thanking Christ for the BBC / A stupid fucking place to be. And there’s beauty and mystery, as well. The ice wagon flies down the alley. There’s a Tesco on the sacred ground / Where I pulled her knickers down / While Judas took his measly price / As Saint Anthony gazed in awe at Christ. The singer gives his love a goodnight kiss. He takes her by the hand, they walk; he dreams they’re walking on The Strand. That night, Rain Street went on for miles.

It’s raining now, as I write this. The Christmas lights of my neighborhood are sparkling off the wet pavement. I can smell woodsmoke from someone’s chimney, laundry—the fake floral of dryer sheets—from one house, and dinner—something with beef, a roast or a stew—from another. A drunk man is pacing around in front of a house across the street, muttering angry words into his phone. It’s raining as I write this, and I’m drinking a whiskey. Bless me Father, I have sinned. Would I live my life over again? Make the same unforgiveable mistakes? Yes, given half a chance. Tonight, on Rain Street, somebody smiled.

Further listening:

The Session: The Pogues & The Dubliners (with special guest Joe Strummer)

Spider Stacy and The Pogues perform “The Parting Glass” at Shane MacGowan’s funeral

Etc.:

I recently watched Crock of Gold, and Shane said something like: Everyone was always calling me a poet—but if I was just a poet, why did I bother to write music? Well, Shane, you were a great songwriter and musician. But you were also a fucking poet.

The line in “Rain Street” about the ice wagon—Down the alley the ice wagon flew—is a reference to the Doors version of “Who Do You Love?” And I knew that. What I didn’t know until I started writing this piece was that I’d been mishearing the lyrics to both songs for decades. I always thought the line was: Down the alley I swagger through. And to be honest, I think I like my misheard version a little better.

A friend of mine texted me when Shane died about how he had last rites administered and said "not very punk but So Irish"...my response was that some people some people are so punk that they transcend the definition, whereby literally ANYTHING they do IS punk...Shane was one of those. (And Joe was another...the best are all like that...)

The ice wagon line was in the original "who do you love", not added by the Doors, George Thorogood, or anyone else.