[these pieces (in slightly different form) were written in 2015, and were originally published at Witchsong in four installments]

Track #1: “Reckless Heart”

I was born reckless / with a reckless heart

—The Reckless Hearts, “Reckless Heart”

It’s never just about the music. It starts with the music, the music gets inside you, hot flashes of noise rushing through your veins, but next thing you know you’re living inside of it, wearing it like a jacket. It starts with the music, but then it’s the dirty bathrooms of bars, the sun rising all peachgold as seen from your best friend’s apartment; it’s the smoke and the sweat, the rails of drugs and the rail drinks, the salty lips of all the boys and girls you’ve kissed. There may come a day when you stop going to as many shows, a day when your record collection has grown to include other kinds of music, but you can’t shed it that easily. Because it started with the music, but became your whole life—and you can stop the girl from going to Kenosha, but you can’t take the Kenocore out of the grrrl.

The first time I went to a show in Kenosha was April 1997. Madigan and McKenna and I climbed into McKenna’s dad’s van, and he drove us twenty minutes south. On the way, we listened to the demo tape of a band from our town. The music was alright, I suppose; dreamy indie-folk with a horn section and cryptic lyrics about junebugs and constellations, but it didn’t move me. I was too nervous, that evening, too full of sharp-edged shattered feelings to be moved by something so mellow. I wasn’t nervous about the show, so much, as I was about who I was with—Madigan and I were crushed out on the same boy, and it made things awkward between us. I was too nervous to talk on that twenty-five minute drive, so I listened to Madigan and McKenna’s idle chatter, ignored the music, and stared out the window at the rain. Oh, that Midwestern April rain, dousing everything with gray and chill-damp when you just want it to be spring already. (It is always raining in my memories.)

The show—in the grand tradition of kids, punks, and punk kids putting on shows at any place that will let them use the space—was at the Polish Legion. We hung outside for a while. I wished I had a cigarette, had something to do with my hands and my nervous energy. The April drizzle coated our hair and skin and clothes. McKenna didn’t have a discernible style, she just wore whatever jeans and long-sleeve shirts were on sale at the mall. Madigan had a thriftstore sweater/cat’s eye glasses indie-emo girl look. I guess I looked the most punk out of all of us—messy hair, a camouflage t-shirt with the sleeves cut off, combat boots, a chain around my neck. Old Polish men who were there to drink piwo gave us sideways looks, then shrugged and went on their way. Inside: big room, wood floors, wood-paneled walls, likely used as a meeting and banquet room most of the time. A handful of kids milled around waiting for the music to start, a few adult supervisors sat on metal folding chairs set up to one side of the room. A few more kids were on the other side of the room in the area that had been taped off to designate a stage, plugging guitars into amps and testing mics.

Finally, the music started. The first band—the band we were there to see—was our friend Jordan’s band, Skadatel. It was the late ‘90s, and the third wave of ska was in full swing; it was also the time period when every other ska band had to have the word “ska” somewhere in their band name. Hence, Skadatel. They had two vocalists—a boy and a girl—and played fun, danceable songs. I didn’t yet know how to skank, so I twisted in place and bopped my head.

The other bands that played that night, I don’t remember their names. But they were punk, hardcore, Kenocore. And they were magic. And the dancing kids were magic—the boys (and one girl) who started a circle pit and became a single, whirling organism made of studs and chains and denim and leather. My god. I wasn’t brave enough to slam dance, but my heart slammed against my ribcage in time to the music.

Between bands, I sat down on one of the folding chairs. I talked to Madigan. We talked about one of our mutual favorite bands—Sleater-Kinney. We thought we saw our mutual crush—we’d both told him about the show—but it turned out not to be him. It was okay that he wasn’t there, we agreed. It was more punk rock than the stuff he liked. He was into emo, math rock, post-hardcore, whatever, and thought that most straight-ahead punk and hardcore bands were too generic. When the next band started, I went and stood near the pseudo stage again. Far enough away that the slam-dancers wouldn’t crash into me, but close enough that I could feel their adrenaline, close enough that I could feel the buzz from the PA and the beat of the drums in my teeth, in my bones. Forget that boy I had a crush on. He might have thought the music was generic, but for me, it was everything. It was the 1-2-3-4, it was the raging inferno of my teenage lust and hate, it was what I’d been waiting for my whole life. I’d started listening to punk at a young age, but that night was the first time I’d been to a real punk show, the first time I’d been that close to the energy and the heat. “Next time,” I thought, “I’ll be the girl in the pit.” No more waiting, I was going to become part of it. I use romantic relationships as a metaphor for everything, so let me put it another way: I had been flirting with punk for years, but that night, I declared my undying love. That night, I stick ’n’ poke tattooed “Punk Til Deth” on my reckless fucking heart.

Track #2: “Punk Life”

The punk life / it keeps me goin’

—Pistofficer, “Punk Life”

Not too long after that night, I threw myself into punk with the fervor only a fifteen year old can achieve. I rid myself of the clothes I still had from my bizarre grunge-hippie phase, such as my flared jeans. (Because, as Joe Strummer once said: “Like trousers, like brain.”) I bought an Exploited “Punks Not Dead” poster at the record store downtown, and taped it to my bedroom wall. (This caused some hilarious arguments between myself and my mom, but that’s a story for another time.) And I wrote in my journal: “I wanna start hanging out in Kenosha. All the cool punk rock guys are there.”

I wrote that because of the show I’d gone to, and also because every time I went to Kenosha, I saw some punk rock boy, all chains and dirty, ripped-up pants, loitering on the steps of some building or other. There were lots of rude boys there, too, decked out in two-tone creepers and porkpie hats, plus the skinheads in boots and braces. There were punks and rudies in Racine, but I didn’t know any of them yet, and for the most part it seemed like our coffeehouses and YMCA shows were overrun by emokids. Don’t get me wrong—I liked much of the music known as emo at the time (when I was being self-deprecating, I referred to myself as an emokid). I still hadn’t gotten over my crush on the emo boy. But I had grown tired of Emo as a Thing. When you boiled down the complex noise and poetic lyrics, they were about how brokenhearted the poor, sensitive straight-white-boy singer was. At least punks have the tendency to be somewhat aware of the world and its ills, and the music reflects that. It’s more “fuck racism, fuck poverty, fuck religion, fuck you,” whereas emo is more “my girlfriend dumped me and I’m really, really hurt.” And at least in the punk scene it is somewhat acceptable for girls to be just as dirty, loud, and angry as the boys are.

And, well, I was more drawn to punk—to its aesthetics, its sound, its trappings. Crushboy notwithstanding, I found punk boys more attractive than emo boys. Black leather jackets covered in studs, tight black jeans with the knees all worn-out and shiny, and mohawks dyed unnatural colors, were sexier to me than ill-fitting thriftstore clothes, Mr. Spock haircuts, and striped Ernie shirts. Not to mention the punk rock girls; spiky hair that I wanted to run my fingers through, patched-up hoodies, little plaid skirts worn with fishnet stockings and big stompy boots and all that jewelry like armor… (Every time I saw a punk rock girl, I thought: “Do I want to be her or make out with her?” Usually, it was both.) I was drawn to the sound of punk, which had, to quote Rebecca Solnit, “a tempo and an insurrectionary intensity that matched the explosive pressure in my psyche.” And its trappings, the things that punks did when they weren’t playing music, those appealed to me, too—getting wasted, smashing shit. I know, those are some of the more boneheaded aspects of punk, but god, they were great outlets for the explosive pressure in my psyche.

I spent years trying to figure out why Kenosha had more of a punk scene and Racine had more of an emo/indie rock contingent. When you look at the towns, they don’t seem like they should be that disparate. They’re only ten minutes apart. They’re both medium-sized cities in southeastern Wisconsin, on the shore of Lake Michigan. They were both once company towns—Kenosha belonged to the American Motors Corporation (later Daimler-Chrysler-Jeep), Racine to Case and Johnson’s Wax. They’ve always had a rivalry—each town claiming that the other is worse—which seems silly to outsiders. Once, while I was riding the Metra train from Chicago back to Wisconsin, someone across the aisle from me asked if I was from Kenosha. “No,” I said, “Racine.” “Eh, not much difference, is there? They’re both dirty old towns.” In recent years, Kenosha has been revitalized in a way Racine hasn’t, but back in the ‘90s, they were both rundown. I eventually came up with a theory to explain the Kenosha punk vs. Racine emo thing. It was that Racine, being closer to Milwaukee, was more influenced by the Milwaukee scene (which, in the ‘90s, leaned more toward the indie/emo end of the spectrum). And Kenosha, being closer to Chicago—as well as being one of the stops on the Union Pacific North Line of the Metra (Chicago’s commuter train system)—was more influenced by the Chicago scene (which leaned more toward the punk/hardcore end).

But in 1997, when I wrote that journal entry, I didn’t care why Kenosha had the punk scene. I only knew I had to start hanging out there. And I did. I convinced my parents to drive me, or I took the bus. By 1998, I was driving there by myself. Over time, Kenosha began to feel more like home than Racine did. I felt at home in the half-dead downtown, walking the gray streets, gazing into empty storefronts. I felt comfortable sitting forever in one of the many 24-hour diners, where I drank coffee until I was twitchy and hyper; often, a punk showed up and talked to me, or at least gave me the punk rock nod—that silent gesture that acknowledged “you’re one of us!” In Kenosha, I felt like I was one of the punks, part of the scene. I felt more at home there because I didn’t live there, because I had no history, yet, with the people there. I could be who I wanted to be, rather than the person I was expected to be. I went to as many shows as I could. Sometimes, Chicago bands came up to play shows in Kenosha, and that was awesome. 1998 was also the year I fell in love with Chicago and the Chicago scene, and I couldn’t always make it to Chicago for shows, but I could usually find a way to Kenosha. I saw Chicago bands like The Arrivals and Deal’s Gone Bad, and local bands, raging hardcore acts like URBN DK, Pistofficer, and Despite. I lost myself in the pit. I flirted with yummy yummy punk rock girls and boys. I found the secret places to get wasted, and the older punks who didn’t mind buying a teenage grrl a 40 oz. bottle of malt liquor in exchange for some conversation. I gave them money, they stepped into a corner store and procured booze, then we ducked into alleys or sat on park benches. We drank and smoked cigarettes, and talked. I told them about my favorite bands, the ones that weren’t from Kenosha or Chicago, and they affectionately teased me for being so into pop punk. And they told me stories. Stories about how much wilder the Kenocore shows were back in their day, or stories about their brushes with the legends of Kenosha punk. There were two names I heard so often, they got burned into my brain: Dean Dirt and Beautiful Bert.

Track #3: “Isn’t Life Crazy”

Lately, people have been calling us old-school / but youth is an attitude, fuckers

—10-96, “Isn’t Life Crazy”

Dean Dirt [Dean Lipke] was the frontman for Kenosha punk legends 10-96 (10-96 is a police code, meaning that the officer is dealing with a mentally disturbed subject). From my earliest days as part of the scene, I had people tell me: “You want to know the real Kenocore shit? You have to see 10-96.” I mean, they started in ‘83, and were still going strong in the late ‘90s, and that alone says something good about them. When an underground band keeps going that long, you know they’re doing it because it’s what they love to do. That intensity and drive is worth more to me as a fan than all the record deals and critical acclaim in the world. I only got to see 10-96 once, in early 1998, and they ripped the place apart. Bone-shattering drums, throbbing bass, blistering guitars, and songs with that pure hardcore rage, they had it all. Dean, especially, impressed me, because he was pushing forty and still had so much ferocious energy. He dove into the crowd and put his whole heart into it, screaming: They’ve been trying to put us down / but we’ve got too much heart. Youth is an attitude. Punk rock, don’t stop. That was the only time I got to see 10-96, and I never met Dean—he passed away in November 1998. But Dean and his music have been a huge part of my life. 10-96 are the Kenocore band I listen to more than any of the others. Also, I still run into people who played in bands with Dean, or knew him from being part of the scene. Though he passed away years ago, he touched enough people’s lives that his presence is still felt. If you spend enough time in Kenosha, you’re bound to hear so many stories about him that it’s like he’s still around.

In early 2009, I was down in Chicago visiting a friend of mine. We’d both recently had our hearts broken (mine by a punk boy from Kenosha!), and decided the best cure for it was to put on our reddest lipstick, get wasted, and slam to some good old-fashioned punk rock. At the club, we drank shots of whiskey and pitchers of beer, and watched the opening band set up. “Wait a second,” I said, “I recognize those guys.” It was Pistofficer, a Kenocore group of drunk punks. I laughed. I would run into guys I’d known since 1998, guys who were friends with the fella I was trying to forget, guys I often saw at the bar, guys I used to do drugs with. A few songs in, they announced: “This song is for a friend of ours who passed away.” I turned to my friend, said: “If it’s someone from Kenosha, it’s gotta be someone I know, too.” Sure enough. “This one’s for Beautiful Bert,” they said, and played “The Bert Song.”

Beautiful Bert [Brian Phillips] fronted many bands over the years, including The Luscious Ones, The BB Slags, and The Crotch Crickets. I heard tales of his onstage antics—heard that the things he did while performing rivaled the likes of Iggy Pop and GG Allin—years before I ever saw him live. The stories did not lie—on stage he was gross, he was in your face, and he was unforgettable. (I once saw him shove a microphone in his butt crack. Unpleasant, yes, but definitely unforgettable). Even without those antics, he would’ve been a frontman to watch. He had a demon scream and a guttural growl and a larger-than-life personality that had nothing to do with his large size. Speaking of GG Allin—Bert knew him, and GG sometimes played drums for Bert. I’ve never been a GG fan, but that’s punk history, right there.

He passed away in early 2008, but I did not know about it until that night in 2009. It surprised me that none of my Kenosha friends had thought to tell me, and I found myself mourning a year late. I mourned the punk scene’s loss of yet another phenomenal frontman, and I mourned his presence in my life. We weren’t close friends, but he was one of my favorite acquaintances. Sure, he could be a drunk asshole on occasion, but who among us has not been a drunk asshole on occasion? And he could also be a total sweetheart. He’d walk into the bar, share a crazy story and grace me with his charming missing-toothed smile, and when he’d ask me for a cigarette, I’d give him two, just because. He had passion, and he lived it. After Pistofficer’s set that night, my friend and I stepped outside for a cigarette. I poured the rest of my pitcher of beer onto the cracked pavement, in memory of Beautiful Bert. As Korye Champion wrote in Art is Dead zine: “Bert was basically my punk rock idol. I knew I’d never get to meet Joey Ramone or Johnny Rotten, let alone hang out with them and shoot the shit. I had Bert.”

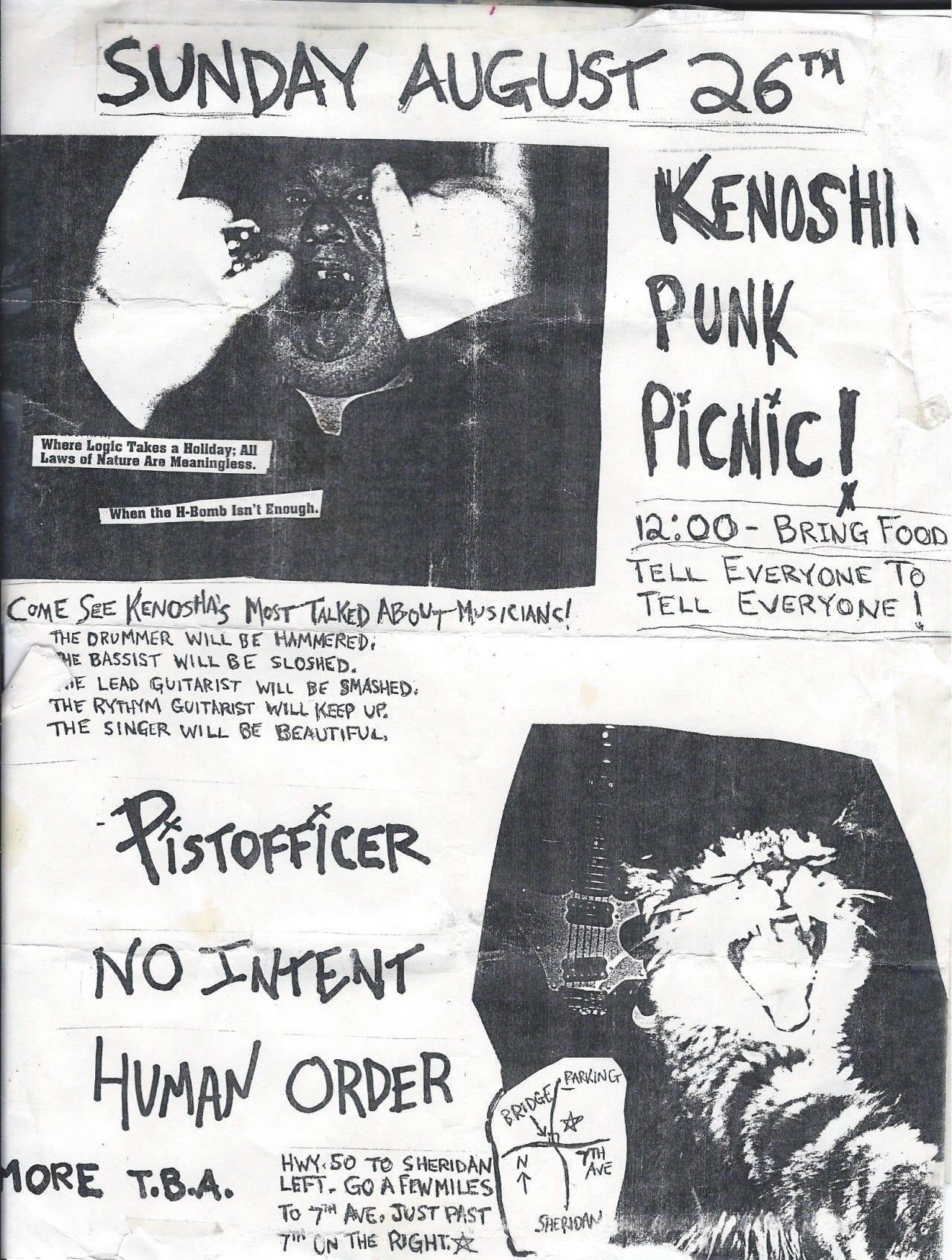

In the decade between when I first discovered Kenosha punk rock and when Bert passed away, I became a full-fledged part of the scene. I saw 10-96 and The Luscious Ones. I saw Pistofficer, URBN DK, Despite, Human Order, and a hundred other bands that I’ve forgotten. I went to shows in basements in town and in barns out in the rural parts of Kenosha County. I went to the Punk Piknik almost every year (back when they held it in a tiny picnic hutch by the lake). I went to shows at The Port, and Hattrix (the CBGB of Kenosha). I did drugs with the boys in the bands, kissed every punk rock boy and girl that fell into my lap. The music got inside me, and then I lived inside it. By 2000, most of the Kenocore people knew me by sight, if not by name. I remember walking to the gas station with my girlfriend, to buy cigarettes, and the clerk recognizing me. I was hard to miss, with my bright-red Chelsea cut hair, and I had a Despite patch safety pinned to my hoodie. “Oi!” he said. “Kenocore!” We accept you! You’re one of us!

Six years later, at a time in my life when I thought I’d given up punk, I was visiting my Kenosha pals. As I sat, sipping my whiskey, an older KHCP dude approached me. He didn’t know my name, but he knew he’d seen me at a lot of shows (and at the bar) over the years. That night, I had on a vintage dress and a clutch of fake pearls—not your usual punk rock girl ensemble—but he never once questioned my right to be part of the scene. In fact, he looked at my tattoos and said: “You’ve got an anarchy tattoo and a Clash tattoo. You’re like, an old-school punk and shit.” I smiled, because if this man who was at least a decade older than myself and was in a band with former members of URBN DK thought of me as an old-school punk, I guess that meant I was. I smiled, because, despite my vintage dresses and my protests that I was no longer a punk—let’s sing along with Jawbreaker: save your breath, I never was one—I couldn’t shed it that easily. You can give the girl an accordion and some fake pearls, you can have her stop going to as many shows…but you can’t take the Kenocore out of the grrrl.

Track #4: “She Loves Rock’n’Roll”

Whoa-oh oh oh oh / she loves that rock and roll

—The Yates Kids, “She Loves Rock’n’Roll”

I don’t go to shows so much these days. In Kenosha, or anywhere. Three weeks after I left California and moved back to my southeastern Wisconsin hometown, my son was born.

Having a child makes it much harder to find the time to go to shows, or to go out at all. I’m also broke a lot of the time, and can’t always afford even a five dollar cover, not to mention the cost of all the drinks I’d like to buy when the show is at a bar. Granted, I’ve been broke for pretty much my entire adult life. In my younger days, though, if it was a choice between eating that day or going to a show, I usually chose the show. I’m not willing to do that anymore. I want different things than I used to.

Nowadays, when I drive south to Kenosha, I’m most often going to my best friend’s apartment. We talk about everything, work on art projects, have two-person dance parties to Beyoncé and Rihanna (or Vana Mazi and Gogol Bordello, depending on our mood). When I have the time and money to go out, I’d usually rather go to a poetry reading or a museum; to a sushi restaurant or a nice quiet bar where I can drink fancy cocktails and listen to jazz. I know, I know.

I haven’t given the punk life up completely, though. A few times a year, I wind up at Hattrix or The Port or some other Kenosha bar, in the crowd to see a long-running Kenocore band like Pistofficer or the Yates Kids or a newer one like Republicans on Welfare. And every time, something happens to remind me that the undying spirit of Kenosha punk rock will always be part of me.

In February 2013, I was at a show in Milwaukee. Most of the bands were Milwaukee bands, but one band was from Kenosha—Pistofficer, of course. Before they played, I stood outside smoking with some pals. I overheard someone ask, “Who’s playing next?”

“Some fucking Kenocore band,” was the response.

“Hey, fuck you, don’t talk shit about Kenocore,” I said. Though I’ve never lived in Kenosha, it feels like home to me, and I am fiercely protective of it. During their set, I went a little nuts in the pit. I slipped in some beer (side note to any boot designers or manufacturers who might be reading this: please make boots that won’t slip in spilled beer!), fell down, and hurt my left ankle. I figured it was a sprain—I’ve sprained my ankles dozens of times. I got out of the pit, found a barstool to sit down on, pounded a couple shots of whiskey. As soon as the pain subsided, I got right back in the pit. It wasn’t until the next morning, when my ankle was so swollen I couldn’t get my boot on and hurt so much I couldn’t put any weight on it, that I decided to go to the doctor—and found out it was broken. When I told my Kenosha pals that I’d broken my ankle pitting it up to Pistofficer, they said: “You’re officially Kenocore now.”1

In January 2014, I went to Hattrix to see a few bands. One of them was Republicans on Welfare. It was the first time I’d seen them, and they were great, reminiscent of all my old favorite Kenocore bands but not totally derivative. Good, raging hardcore with a side of garage-punk. I danced up front for most of their set, and the pit (such as it was, there were too few people for it to truly be a pit) was mostly made up of girls. A couple dudes bounced in and out, but most of the time it was us girls slamming, skanking, pogoing. I picked up the words to choruses on the fly and shouted along. Toward the end of their set, they did a scorching cover of “Blank Generation” and then I really shouted along. I love anytime a band covers that song. It was written, what, forty years ago and is still the perfect anthem for anyone disaffected. I was sayin’ “let me outta here” before I was even born…it’s such a gamble when you get a face.

When the music ended, my friends and I stayed a while longer, drank more, talked to some people. I talked with a cute little punk dude (mussed-up hair, striped shirt, Army-issue jacket covered in patches). He flirted with me: “I haven’t seen you around here before.”

“Well,” I said, “I don’t get out much anymore, but I’ve been coming to punk shows in Kenosha since 1997.”

He looked down at his feet and said, “Uh, I wasn’t going to punk shows back then. I was seven.”

I thought about the older punks who’d taken me under their leather jackets when I was coming up in the scene, and realized that now I’m one of the old-school punks. And I’m okay with that, because 10-96 taught me that youth is an attitude.

February 2015, I once again found myself on the road to Kenowhere. It’s a route I’ve traveled often, south on Highway 32, with the frozen lake to my left and the train tracks to my right. I wondered how many times I’d driven down that road over the past eighteen years, and decided it must be hundreds. Yet hundreds of drives later I was still just as excited about the night ahead of me as I’d been the first few times. I thought about all the drinks to be had, the songs to be sung, and the faces to be seen; I was even looking forward to seeing the familiar houses that mark the outskirts of town and the neon lights of the same old bars. I thought of that person on the train all those years ago, who told me that Kenosha was just another dirty old town, and I thought: “Yeah, well, it’s my dirty old town.” I thought of that journal entry I wrote at age fifteen, about how I wanted to start hanging out in Kenosha because all the cool punk rock guys were there, and I laughed, realizing I’d probably made out with at least half of them in the years since.

The Port was packed with punks and hippies and goths. I couldn’t get anywhere near the stage area, and I had to hold my plastic cup in the air so that the people dancing in front of me wouldn’t bump into it and spill my drink. Donoma played first. They’re one of my current favorite Kenosha bands, and they’re not even technically punk. They have the fierce energy of punk, but they are also glam and rock and cabaret, and they stand out because of Stephanie Vogt’s killer vocals and Nick Campolo’s electric violin.

The Yates Kids were the last band of the night, and though I’ve seen them a dozen times or so, they put on a good show every time. I was far away from the stage, and there was no room to really dance, so I pogoed. It was perfect music to pogo to—the kind of fast, rhythmic, raw punk rock ’n' roll I love. After the show, I hung around for a while, not yet ready to call it a night. I got hugs and high-fives from friends I hadn’t seen in years. Someone that I didn’t think would even remember me bought me a beer. I looked around at the crowd, at the faces I knew and the ones I didn’t know. I was glad to see a huge crop of younger punks. It does my heart good to know that, to paraphrase the World/Inferno Friendship Society, the kids do still sing and dance, drink and fuck, and smash it up in the homeland. And I was glad to see the ones who, like me, are now the old-school punks. Some of them I used to see at shows or diners or bars multiple times a week, and now most of us have families or full-time jobs and don’t get out so much anymore—but most of us are still here. Before I left, I went to the merch table and bought a patch: white ink on black fabric, the letters KHCP spaced between crossed bones, with banners across the top and bottom that read “Kenosha Hardcore.” I’ve sewn it on the back of my black hoodie, so no matter where I go I have a little scrap of my adopted homeland with me.

If you ever find yourself in southeastern Wisconsin, think about going to a punk show in Kenosha. And if you do, let me know, and I’ll see you in the pit.

During the writing of this piece, I heard the news that Frank Lenfesty, Jr.—frontman of Pistofficer and mainstay in the KHCP scene, had passed away. I like to imagine he’s now with Dean Dirt and Beautiful Bert, tearing it up in that big slam pit in the sky. We’ll miss you, Frank—and whenever the weather gets cold and my left ankle starts to ache, I’ll think of you.